It is easy to see monumental differences between faith and science. The faithful are powered by belief. Scientists demand evidence.

Dekila Chungyalpa sees similarities. Namely, she sees a planet that both share and want to protect.

What if the two groups combined forces to protect the earth? Faith leaders had already begun the work in their own corner of the world over the past few decades. But what could be accomplished together if scientists — from the fields of environment, health and psychology — were to join them?

That’s the goal of the Loka Initiative, a new interdisciplinary collaboration among UW–Madison programs that is housed in the Center for Healthy Minds and directed by Chungyalpa. Campus participants include the Center for Religion and Global Citizenry, Division of Continuing Studies, the Global Health Institute, the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and the Religious Studies Program.

The idea

Chungyalpa first began exploring the idea while leading Sacred Earth, an acclaimed faith-based conservation program at the World Wildlife Fund. The discussion expanded in 2011 to include UW–Madison’s Richard Davidson, director of the Center for Healthy Minds, John Dunne, distinguished chair in contemplative humanities at the center, and Jonathan Patz, director of the Global Health Institute. In 2019, the Loka Initiative became a reality.

“What drove me from the beginning was this realization that the conservation community had a blind spot because we didn’t see how influential religions were at a global scale,” says Chungyalpa. “We didn’t realize how important they are as a stakeholder collectively.”

The initiative gets its name from an ancient Sanskrit term meaning one or many worlds. Its mission is to support faith-led environmental and climate efforts locally and around the world by helping build capacity of faith leaders and culture keepers of indigenous traditions, and by creating new opportunities for projects, partnerships and public outreach. An important part of its focus is on traditional ecological knowledge, also called indigenous knowledge or Native science, referring to the evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous and local peoples over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment.

“I think there is something that can be gained from all religious traditions,” Chungyalpa says. “However, there are few avenues that allow for traditional knowledge and wisdom to flow into the scientific secular world. And, yet it is clear that both sets of strengths — scientific and ethical — are needed for us to solve the environmental and climate crisis.”

Gaining wisdom from studying ancient traditions is something familiar to the Center for Healthy Minds, where researchers and scholars search for what constitutes well-being.

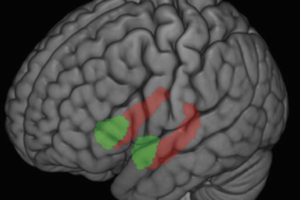

“The reality is we underestimate the complex, interdependent set of factors that shape our emotional and physical health,” says Davidson. “Although we’ve studied many ‘environmental’ factors such as childhood experiences, relationships, access to nutrition and health care, we’re in the infancy of truly grasping how our literal physical environment — access to natural spaces, quality air, clean water — can influence our well-being, and in reverse how our own mental states affect how we treat the environment.”

In 2018, Davidson, Dunne and Chungyalpa convened a group, including His Holiness the Karmapa, a Tibetan Buddhist leader who visited UW–Madison and participated in planning discussions around an education and capacity building platform based at the university. They talked about how environmental protection efforts and climate action required a bridge to be built between faith leaders and scientists, scholars, policy makers and other experts in the secular world.

“It is clear that both sets of strengths — scientific and ethical — are needed for us to solve the environmental and climate crisis.”

“Science needs religious leaders to help convince people that environmental protection is an urgent moral issue and not only an economic or political one,” His Holiness the Karmapa said. “Without science, people lack the knowledge on how to solve environmental or social problems. But if you can add religious support to scientific expertise, you are able to generate greater courage and commitment among people to address these issues. For this reason, science and religion must find ways to work together.”

A similar sentiment inspired Paul Robbins, dean of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, to become involved in the initiative as a scientist and UW–Madison campus leader.

“For us, the last thing you want to do when it comes to people is to start with something abstract called the ‘environment.’ That’s a dead end,” Robbins says. “You have to start with what people value. And if faith communities are missing from the conversation, we’re doomed — because values and experience exceed anything we can tell them about the environment. They can only tell us.”

Meeting of the faithful and scientific minds

An opportunity for sharing across faiths and science sprang to life earlier this summer, when people came from as far as Zambia, Indonesia, Italy and Israel to Holy Wisdom Monastery in Middleton for “Faith in Action for a Flourishing Planet.” The two-day symposium examined global progress in environmental and climate change strategies while investigating the potential for faith-led environmental action by building understanding, motivating change and creating practical goals.

The chance to sit down with community leaders provided a rich opportunity not present in other academic conferences, and the more tangible potential of actually acting and collaborating.

“There was a shared sense of purpose. Everyone agreed that there’s something happening on a social movement level, but there are different perspectives and levels of impact to figure out,” says Jordan Rosenblum, the Belzer Professor of Classical Judaism and the director of the Religious Studies Program at UW–Madison. “This meeting had more of a sense of potential for action, which isn’t something I’ve felt from other events.”

And many faith leaders and activists who participated see the clear role faith can play in caring for the planet.

“We believe that people of faith have a great responsibility to stand up for environmental and climate justice, and to address the concerns and calamities of the poor and marginalized communities,” says Huda Alkaff, founder and director of Wisconsin Green Muslims. “They have the lowest ecological footprints, yet they are most impacted by natural and unnatural disasters. It is a moral issue.”

“Science needs religious leaders to help convince people that environmental protection is an urgent moral issue and not only an economic or political one.”

Many faiths and traditions were represented at the symposium — Buddhist, including Zen and Tibetan; Christian, including Catholic, Baptist, Evangelical, Episcopal and Lutheran; Hindu; Islam; Judaism; Sikh; and Sukyo Mahikari. Indigenous leaders attended, representing the Anishinaabe; Diné (Navajo); Ho-Chunk; Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation; Mayan; Menominee; and Tsétsêhéstâhese (Cheyenne).

“All of us, Christian or not, must recognize our responsibility and obligation to protect Creation from the catastrophic effects created by climate change,” says Sally Bingham, Episcopal, founder of Interfaith Power and Light.

The room was full of faith — and science.

“For me, the goal of the symposium was to bring together faith leaders who have been leading environmental and climate work on the ground and scientists who want to provide help and apply their knowledge in a way that is practical, and for both groups to hear each other directly on what is most needed from the other,” Chungyalpa says.

The symposium was a chance to talk about what had already been working and what hadn’t. The question of how to get people to care and actually do something is constant. Chungyalpa gets it.

“Apathy can come from being overwhelmed and terrified and not knowing what to do,” she says. “Sometimes too much information can be as overwhelming as too little information.”

That means listening and trying to understand where people are coming from instead of dismissing them outright.

“We humans are, in reality, such an optimistic species. Our assumption is something else is going to stop the environmental and climate crisis — someone else is going to fix this,” Chungyalpa says. “The reality, of course, is it’s going to take each and every one of us.”

And it’s going to take ecological, communal and personal resilience — one of the topics of the symposium.

Taking action

Musonda Mumba flew from Kenya to Madison for the symposium. She worked with Chungyalpa at the World Wildlife Fund and is now head of the United Nations Environment’s Terrestrial Ecosystems Programme. For her, taking action is part of resilience.

Born in Zambia, her environmental work has brought her all over the world. She’s seen significant changes back home and in her travels.

“Something deep has happened in our communities and I think this meeting is a demonstration of knowing that. There’s a realization on this planet — a collective realization that there’s something as humanity we’ve done wrong.”

In March, The UN General Assembly declared 2021–2030 the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. The aim is to massively scale up the restoration of degraded and destroyed ecosystems as a proven measure to fight the climate crisis and enhance food security, water supply and biodiversity.

“All of us, Christian or not, must recognize our responsibility and obligation to protect Creation from the catastrophic effects created by climate change.”

Currently, about 20 percent of the planet’s vegetated surface shows declining trends in productivity, with fertility losses linked to erosion, depletion and pollution in all parts of the world. By 2050 degradation and climate change could reduce crop yields by 10 percent globally and by up to 50 percent in certain regions, according to UN Environment.

“It affects everyone on this planet,” Mumba says. “We want people to commit to this decade.”

The symposium was the first step of many to come for the Loka Initiative. An online noncredit course is being developed that will integrate faith perspectives and traditional knowledge with the latest scientific findings to examine today’s most pressing environmental concerns and livable solutions that can be adopted individually, in faith communities and globally. A book is in the works that will address ecological and climate despair felt by those working on the frontlines of these issues, combining the science of well-being with the wisdom of spiritual traditions.

It can be difficult to care so much when it appears that many others care so little. Chungyalpa is determined.

“One way to wake people up is to say saving the earth is the same thing as saving ourselves,” Chungyalpa says. “It really is.”

-Käri Knutson