In a rare convergence of spirituality and science, the Dalai Lama and a handful of Western neuroscientists met this week at the university to discuss ways in which they can collaborate to conduct research on meditation.

The scientists sought the Dalai Lama’s ideas on studying meditation, the central practice of Buddhism for 2,500 years.

“Our scientific lives have been deeply affected by these interactions with His Holiness,” says Richard Davidson, director of the Keck Laboratory for Functional Brain Imaging and Behavior and UW professor of psychology. “This dialog has motivated us to vigorously pursue research on contemplative practice because we believe it can be beneficial. We hope eventually to take techniques involved in various kinds of meditation out of their Buddhist context and apply them to secular training that may improve mental and physical health.”

Buddhism essentially has the same goal, the Dalai Lama says.

“All human beings have an innate desire to overcome suffering, to find happiness. Training the mind to think differently, through meditation, is one important way to avoid suffering and be happy,” he says.

The meeting, called “Transformations of Mind, Brain and Emotion: Neurobiological and Bio-Behavioral Research on Meditation,” was organized and sponsored by the Mind and Life Institute of Boulder, CO, and the HealthEmotions Research Institute of UW Medical School. The Mind and Life Institute has organized eight similar meetings between Western scientists and the Dalai Lama; Davidson has attended three. HealthEmotions is one of the only research centers in the world investigating the wide-ranging health effects of positive emotions.

In three sessions ending May 22, four scientists told the Dalai Lama about preliminary research they are conducting or designing involving various aspects of meditation.

In addition to Davidson, who is recognized widely as a leader in emotions research, the senior scientists included Paul Eckman, professor of psychology and director of the Human Interaction Laboratory at the University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) and Michael Merzenich, professor in the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences and director of the Coleman Laboratory at the UCSF. Antoine Lutz described the projects he and his mentor and associate, Francisco Varela, have been conducting in France. Varela, head of the Neurodynamics Unit of the Laboratory of Cognitive Neurosciences and Brain Imaging at the Salpetriere Hospital in Paris, was unable to attend due to illness.

“Buddhist monks have known for centuries that meditation can change the mind. Now we are inspired by His Holiness to examine with our technology the precise brain changes that occur with practice.”

The Dalai Lama was deeply engaged in the discussions, peppering (through his interpreters) each presenter with questions that revealed a level of understanding not ordinarily expected from a non-scientist. He readily offered the Buddhist perspective on scientific issues being discussed. Several theoretical questions emerged from the exchanges, which will serve as guideposts for directions in which to proceed in the future, says Davdison.

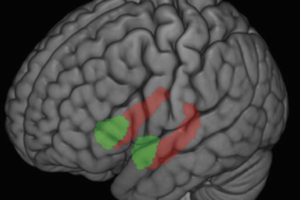

The questions included: Can meditation be used to change brain circuits associated with emotions? Do different kinds of meditation practice produce distinct brain effects? Does the development of certain brain areas through meditation impact physiological factors that may prevent illness? Which areas of the brain are developed in long-time practitioners of meditation? How long does it take before meditation produces significant brain changes?

“One important issue discussed at this meeting involved plasticity of the brain, its ability to change, even during adulthood,” says Davidson. “Buddhist monks have known for centuries that meditation can change the mind. Now we are inspired by His Holiness to examine with our technology the precise brain changes that occur with practice.”

Before the meeting began, Davidson took the Dalai Lama and others on a guided tour of the new $10 million brain imaging facility. The visit included up-close looks at a latest-model functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner, and the accelerator used to make radioactive isotopes needed for PET scans.

Known to have a life-long curiosity about science and technology, the Dalai Lama has expressed keen interest in this sophisticated new technology that can be used non-invasively to examine the effects of meditation. “Wonderful,” he said repeatedly at seeing it. With characteristic humor, he added that he would like to get his hands on tools he saw in the laboratory machine room, where parts for the scanners are made.

The Dalai Lama says he has shunned the warnings of others who fear that science is the killer of religion. Going his own way, as the Buddha advised, His Holiness says he sees many benefits in science.

“I have great respect for science, ” he says. “But scientists, on their own, cannot prove nirvana. Science shows us that there are practices that can make a difference between a happy life and a miserable life. A real understanding of the true nature of the mind can only be gained through meditation.”

The unique collaboration on meditation is just beginning, says Davidson.

“It was clear that His Holiness was deeply interested in and committed to furthering research on the effects upon the brain of meditation practice,” Davidson says. “The scientists are deeply moved to have His Holiness as a kind of collaborator, and we look forward to providing an update on our progress at future Mind and Life meetings.”