When Will Clifton went on a road trip out West with his elderly parents five years ago, he quickly realized something was amiss.

“My mother has always been the keeper of directions, but when I handed her the map, she couldn’t read it,” Clifton says. “I said to myself, ‘She’s not tracking this.’ She couldn’t tell where we were on the map or where we were going. And then her questions got repetitious.”

Clifton learned his parents had not shared with him his mother’s recent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. He was heartbroken to learn on the same trip that his father was also experiencing confusion and memory issues.

“I then gave the map to my father, and he thought we were on the wrong side of the Rockies and could also not track things,” he says.

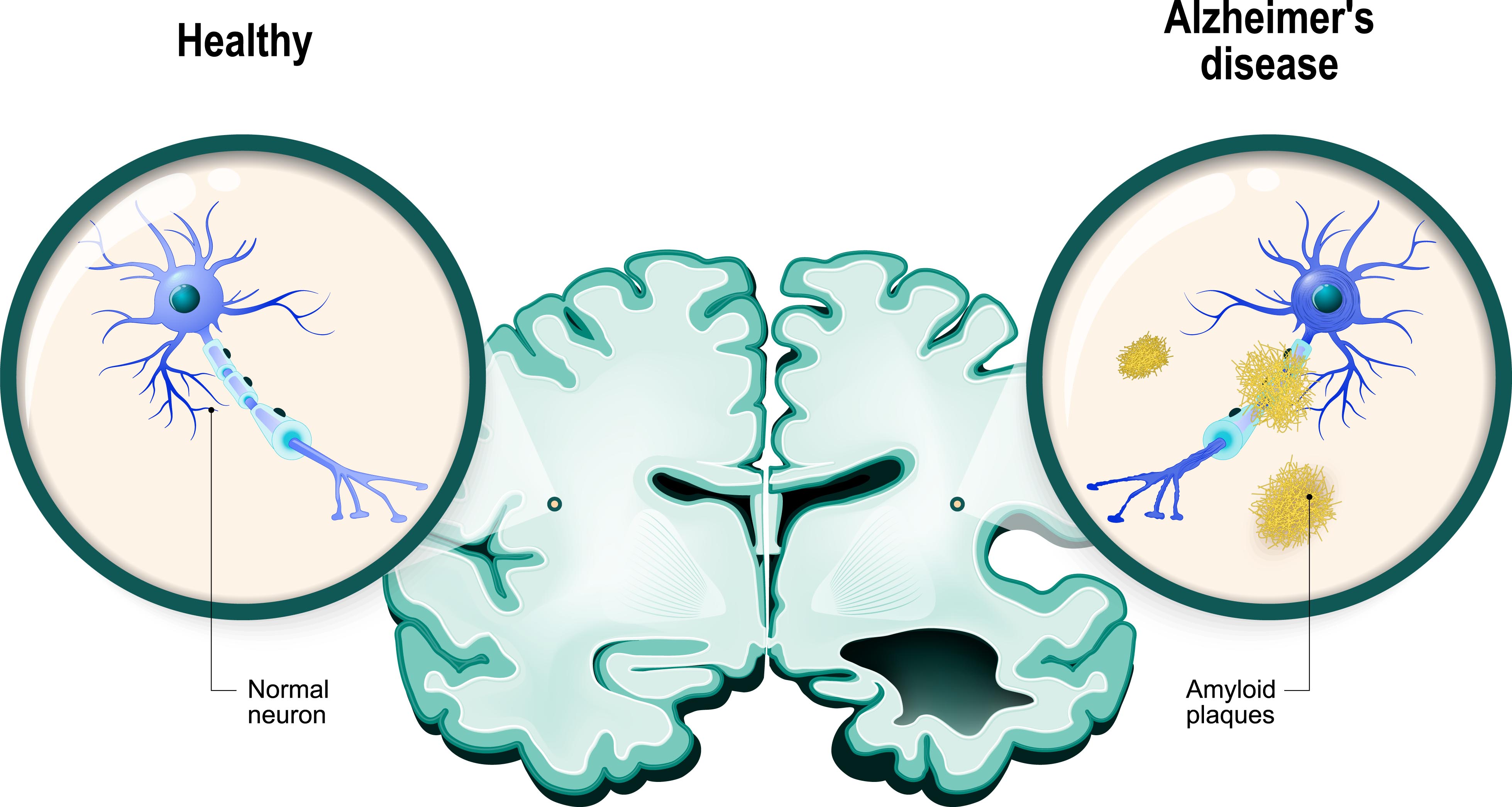

Stories like Clifton’s – where one or more family members develop Alzheimer’s – are unfortunately becoming more commonplace, with the disease becoming one of the top public health crises in the United States and the sixth cause of death. This irreversible, accelerating brain disorder not only impairs memory and thinking, but it can also create emotional hurdles.

“My mother has always been the keeper of directions, but when I handed her the map, she couldn’t read it.”

Will Clifton (left) is a full-time care-giver to his parents Kelly Clifton and Mayre Lee Clifton.

Yet such emotional challenges may hold clues for better treatment and prevention — a reality that has inspired Center for Healthy Minds researchers to collaborate with the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) for a two-year study to examine how emotion may play a role in the development of the disease.

“We’re hoping to learn whether people’s typical emotional responses styles seem to be linked to developing Alzheimer’s,” says Stacey Schaefer, associate scientist at the Center who leads the research. “The goal is to reveal predictors of Alzheimer’s and how we may be able to better develop and target interventions and therapies to help."

The project, funded by the National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Mental Health, will examine how emotional processes may go awry during early stages of the disease. High rates of depression, anxiety, agitation, irritation and mood swings are frequently reported in patients, and the same networks responsible for emotion in the brain are those that are affected by the disease. Though people with depression have a greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, there are many unanswered questions whether emotional responses may be linked to the intensity and timing of the disease, and if one predicts the other.

The team will work with participants between 50 and 85 years old who have previously participated in multiple WRAP lab visits, where scientists have collected brain imaging data, blood samples, spinal fluid and cognitive measures. Most of these participants have a parent who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition, Center researchers will measure people’s emotional responses to stimuli in the lab – like images of cute animals and children, people in love, accident and war victims, appetizing food, etc. – by measuring their facial muscle and brain responses. The team will also look at how these measures of emotional responses relate to memory and cognition changes, and brain data tracking tau and amyloid levels – the tangled and damaged neurons in the brain that are left in the wake of the disease.

“We want to know whether there are signs earlier in the development of the disease or if there are different emotional styles that might increase the vulnerability to Alzheimer’s,” says Schaefer. “This disease’s numbers are astounding. Our health care systems can’t take care of it. Our hope is to find new information to delay, prevent and take care of people who have it in a much more humane way by understanding their emotional problems.”