Neuroscientists and psychologists at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison recently discovered a connection between emotional reactions to stimuli not consciously “seen” and the way we view other, unrelated people in our environment. They found this happens when we are unaware of the initial emotional provocation. This suggests there are regulatory benefits associated with processing emotion and being fully aware of the trigger.

The study, published today in the journal Psychological Science and conducted at the Center, shows that conscious awareness of an emotional trigger decreases the likelihood that an emotional reaction will bias you against other, unrelated targets in your environment.

Their findings highlight a crucial role for conscious awareness in emotion regulation. Conscious awareness is defined here as “conscious access,” or processing an external emotional stimulus with a reportable perceptual experience.

If we are exposed to stressful news in the background of our activities during the course of a busy day – even if we don’t consciously register the information – it can color our judgment of other unrelated attributes of the environment. But the researchers findings suggest that being consciously aware of the stressful news breaks this association, making it less likely this negative response will “spill over” and color our perception of other stimuli.

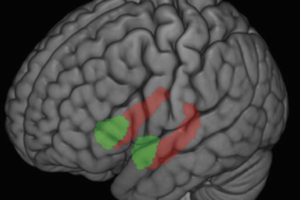

“Even when you’re not consciously aware of an emotional stimulus, regions of the brain still pick up on it and process it,” says Regina Lapate, lead author on the paper and a doctoral student at the Center. “We wanted to know, what are the functional consequences of this? What are the behavioral consequences of those responses when you’re not aware, and how do they differ from when you are aware?”

"Even when you’re not consciously aware of an emotional stimulus, regions of the brain still pick up on it and process it."

Prior studies have shown that when a person evaluates neutral stimuli, like a face or an abstract pattern, their rating of the stimuli is changed if a negative image was presented before it, especially if the image was hidden from view. The popular theory was that a person uses emotional information garnered from the initial stimulus to interpret the subsequent image in a negative way. The subsequent response is thereby biased based on the initial reaction.

“What we found is that conscious awareness breaks the correlation that first emotional reaction and our later evaluations of neutral stimuli,” Lapate explains.

The 46 participants in the study were presented with emotional and neutral stimuli. In half the trials, conscious awareness was manipulated using a visual awareness manipulation method called continuous flash suppression. While one eye was presented with a low-contrast, static image – a fearful face or a spider (emotional), or a flower (neutral) – the other eye was being shown a high-contrast, dynamic block of colors. To measure the magnitude of emotional response to the subsequent images, the researchers looked at whether skin conductance, or sweat, increased. To measure the behavioral impact of the initial response, the researchers asked participants to rate the likeability of neutral, novel faces shown seconds later.

The scientists found that fearful faces increase sweat responses regardless of awareness, and that higher level of sweat responses to a fearful face predicts less liking of a subsequently shown, neutral face – but only if you are unaware of the fearful face.

“Whenever you’re fully aware being shown a fearful face, there’s no association between sweat responses to it and how you evaluate later-presented neutral faces,” says Lapate.

She plans to continue exploring the role of awareness in processing emotion, and understanding how conscious awareness influences activity in emotional-processing neural substrates. This new knowledge may one day have important clinical implications. The findings imply that learning to cultivate increased awareness of emotional information can help people to better regulate their emotions.

“When we go about our lives, our visual system is overloaded, so we’re only consciously aware of a fraction of that information,” says Lapate. “How do peripheral expressions of emotion that may go undetected influence us? How do they affect the brain? Especially when we’re not actively attending to them?”

It may be beneficial to learn to focus one’s attention in different ways in order to process emotion more effectively, for example.

Other authors on the study included Bas Rokers, of UW–Madison and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, T. Li of the University of Chicago, and Richard J. Davidson. The study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-MH43454 and P50-MH069315, awarded to Richard J. Davidson.